Giving and receiving feedback on a script is a critical part of the screenwriting process.

HOW TO GIVE

FEEDBACK

Giving and receiving feedback

on a script is a critical part

of the screenwriting process.

LUKE FOSTER

CenterFrame Team

Your well-intentioned thoughts and notes can be met with a defensive response from writers, though, making you think twice about providing feedback again. Meanwhile, writers can feel frustrated and hurt by feedback that’s too vague or feels overly critical.

Here are some tips for how to give feedback to writers that’s helpful and constructive.

It’s human nature to zone in on the flaws in something. We do it all the time in our daily lives, ignoring everything about the world around us that’s in perfect working order and focusing on the one or two things that are irritating us.

This often happens when people are providing feedback: they launch into the issues in a script that are bothering them and omit to say what they actually like.

This causes the writer to become defensive, as they feel like their work and, by association themselves, are under attack. Since no one has told them which aspects of the screenplay are good, they can assume the whole thing needs to be junked or completely rewritten, and try to fix elements of the script that aren’t actually broken.

So always take the time to go through the aspects of the script you like first, whether that’s particular characters, specific scenes or small moments.

As a writer, there’s nothing more frustrating than receiving feedback such as: “It needs to be sizzling”; “It needs more oomph”; “It’s too dense”…

There’s nothing actionable you can do with these notes. You’re just left with the feeling that there’s something fundamentally wrong with your screenplay, but you’ve no idea what to do about it.

So after you’ve said what you like about a script, be specific about which aspects of the screenplay you feel need more work: “Melanie seemed unnecessarily rude in this moment. Could you soften her attitude?”; “Could you trim down the dialogue in this scene so less is said and more is conveyed through looks and gestures…”

Be specific about what you like as well. Don’t just say things like “I love it. The characters are fun, but…”. Say exactly what you think works in a script, so the writer knows to leave those aspects alone, as well as specifically what they need to work on.

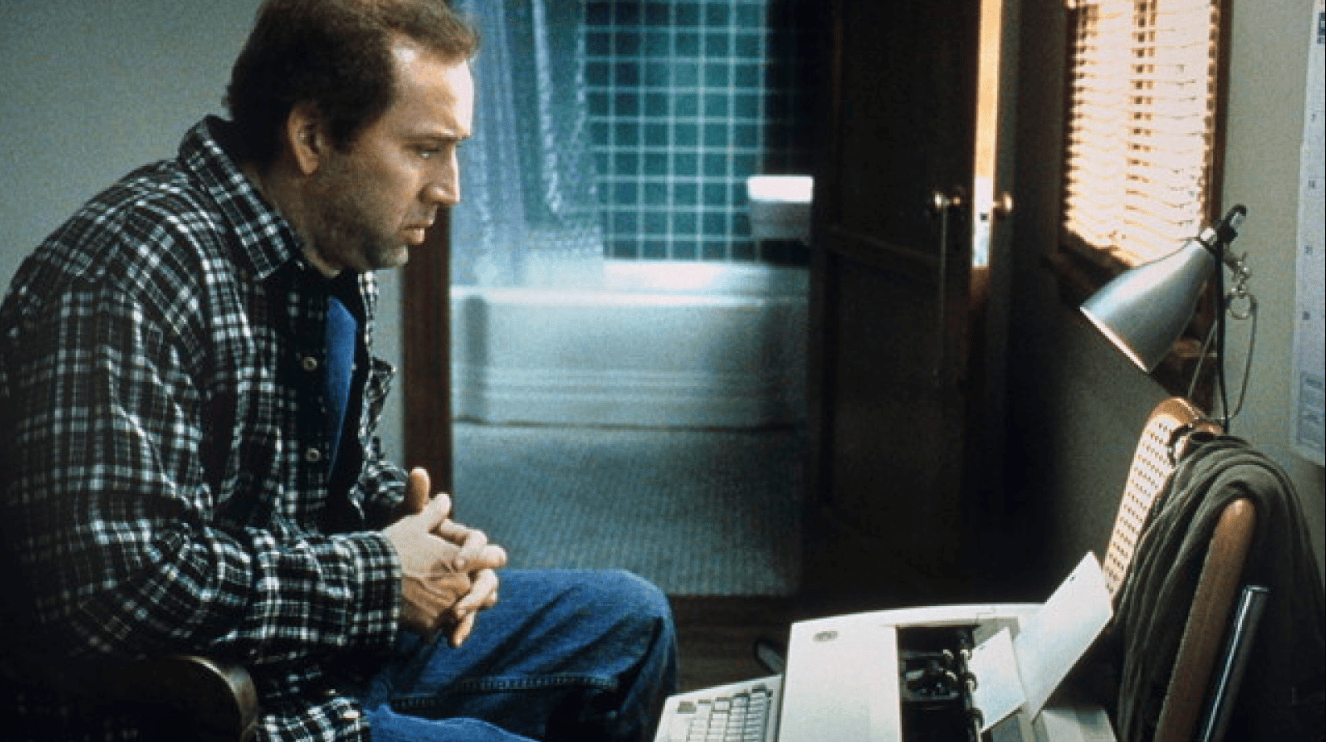

SUNSET BOULEVARD (1950)

After you’ve covered what works for you in a script, you primarily can focus on everything that needs further development. But you don’t want to seem like you’re piling on and pointing out one problem after another.

One way to avoid this is to sprinkle in further positive comments. For example: “In this scene, I really like the way Sandra comes to Terry’s rescue, but his reaction could feel too extreme”.

Another way is to use one part of the script as an example for how to address an issue somewhere else.

For example: “In the scene in the park, I really like the way you subvert our expectations about what’s going to happen. Could you do something similar in the scene in the café, so the scene doesn’t feel too predictable?”

Another aspect of human nature that can easily creep into feedback is the notion that because we think or feel something, that’s the way it is. I think pickle tastes disgusting, therefore pickle is disgusting.

But everyone’s tastes are different. And just because you think a scene in a script needs more pelicans, it’s not a definitive fact that the scene needs more pelicans. It’s just your opinion.

That’s not to say you can’t express that opinion, but try to present it as such. For example, instead of: “Mark is one dimensional”, saying: “Mark feels one-dimensional to me”.

This might seem like only a subtle difference, but it can make your feedback feel less like a criticism and more like your offering market research, which can make the writer more receptive.

A good way to avoid a defensive reaction to your feedback is to phrase as much as you can as a question.

If you tell a writer: “This dialogue is on the nose”, you could get an offended response. But if you ask: “Does this dialogue feel too on the nose?”, it gets them thinking about it, rather than viscerally reacting to your note.

Continuing the example above, instead of: “Mark feels one-dimensional to me”, you could ask: “Does Mark feel one-dimensional?”, or even better: “Could we see different aspects of Mark’s personality, so he won’t come across as one dimensional?”

When people read scripts and provide feedback, they often focus on what they think: this seems logical, but that doesn’t make sense.

But when audiences watch films, while they might think about plot-related logic issues afterwards, in the moment they focus more on how they feel: this part’s sad, this bit’s scary, this scene is getting boring…

So it can be invaluable to a writer to tell them how different parts of the script made you feel, as it can give them an early sense of how an audience will feel watching the film.

If you say a particular element of a script made you feel emotional, they might consider amplifying that aspect, whereas if you say your attention wandered reading a sequence and you lost interest, they could consider cutting that section out or adding more drama and tension.

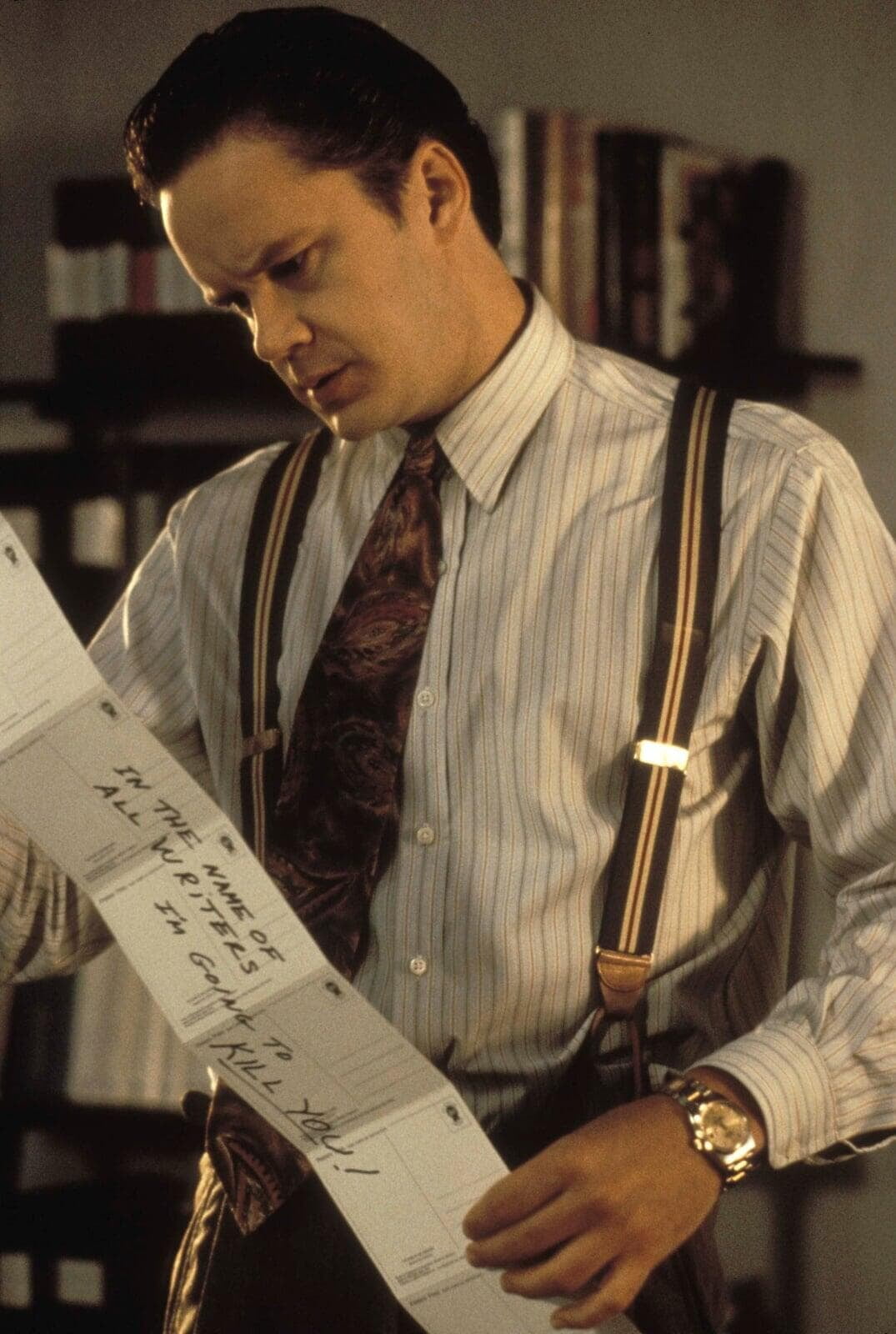

THE PLAYER (1992)

Try to end your feedback on a positive note, even if it’s just a simple reminder about how much you like the overall idea and the aspects of the script you enjoyed.

This helps the writer approach the next draft in a positive frame of mind, feeling good about what works and knowing specifically what they need to address.

LUKE FOSTER

Development Executive | CenterFrame Team

Luke Foster is a screenwriter and Development Executive for Iron Box Films. He wrote the horror comedy Ravers, which premiered at FrightFest 2018 and was released in 2020, including theatrically in North America. He also wrote the comedy drama Betsy & Leonard, for which he won Best Original Screenplay at the Madrid International Film Festival in 2013. Luke hosts the monthly CenterFrame Script Club and has a video essay series on horror filmmaking, Alive In The Morning.

Related articles

You can edit text on your website by double clicking ely, when you select a text box

You can edit text on your website by double clicking ely, when you select a text box

You can edit text on your website by double clicking ely, when you select a text box

You can edit text on your website by double clicking ely, when you select a text box

You can edit text on your website by double clicking ely, when you select a text box

You can edit text on your website by double clicking ely, when you select a text box