BREAKING THE SO-CALLED

RULES OF SCREENWRITING

LUKE FOSTER

CenterFrame Team

When new writers get into screenwriting and start learning about the craft, it doesn’t take long before they encounter certain “rules” they are meant to follow:

Don’t direct on the page. Don’t say: “we see”. Don’t write too much description. Don’t use parentheticals. Don’t use voiceover. Use correct formatting only…

Screenwriting books, script gurus and academic courses love to stress the importance of following these rules when writing a screenplay. As these examples show, though, the screenwriters of successful and well-loved films broke these rules to good effect.

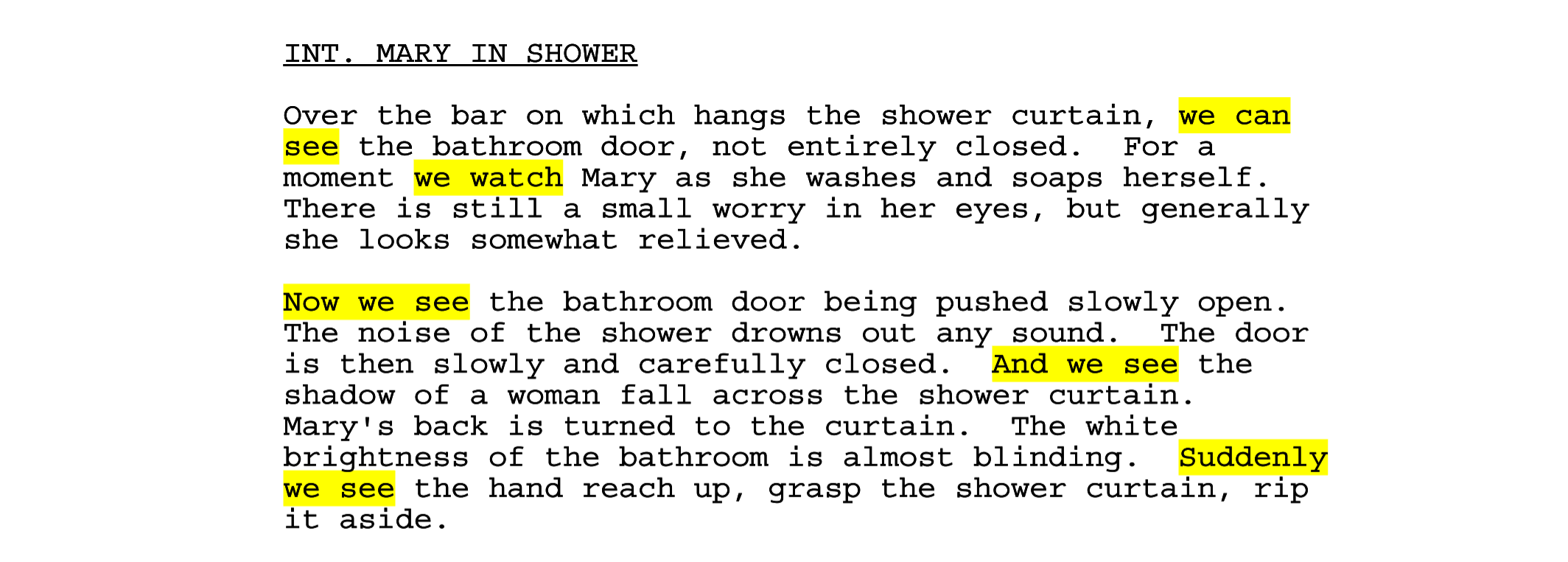

Personally, I find this so-called rule to be one of the most baffling, as the job of the screenwriter is literally to describe what we, i.e., the audience, will see and hear on screen.

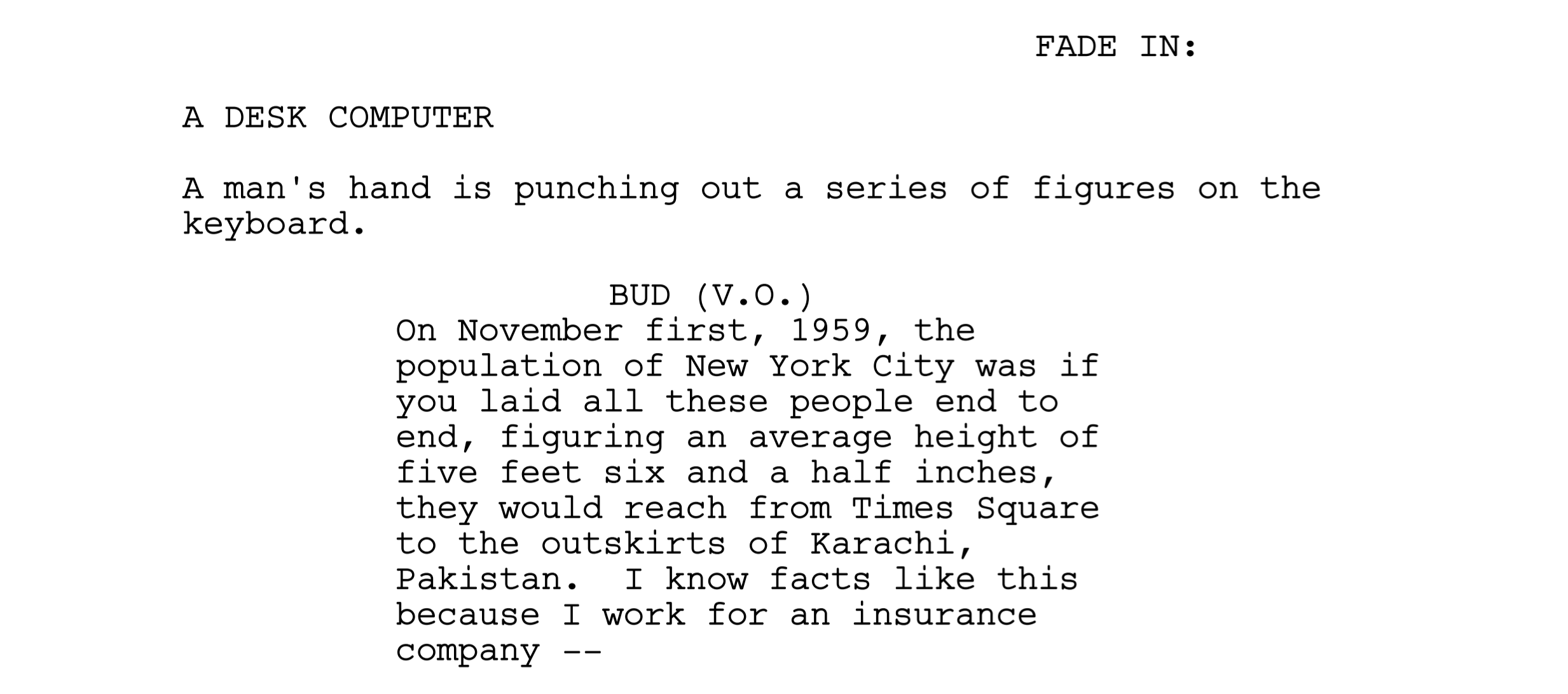

No one seems to have told Psycho screenwriter Joseph Stefano about this rule. His script for one of the most famous scenes in film history, the shower scene, is littered with examples of: “we see”. It even includes a: “we watch”.

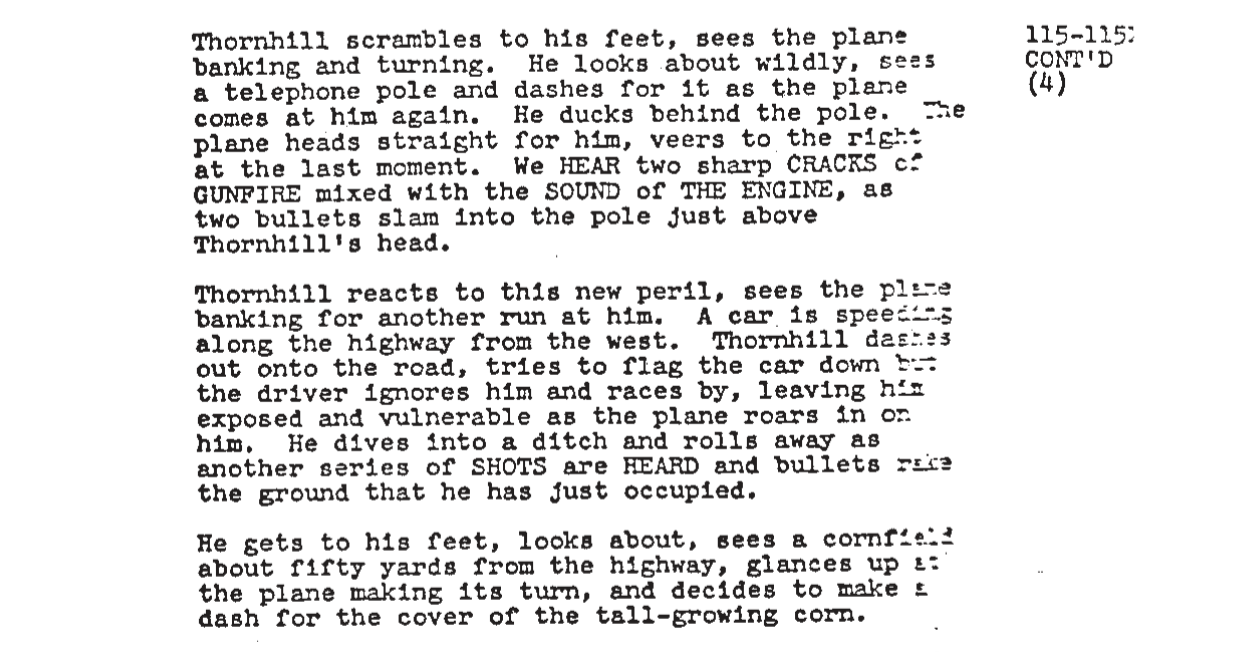

Writers are frequently told that time-pressed producers and executives will only skim the visual description, so keep it sparse and use lots of white space. There is some truth and logic to this and the more economical writers can be in their action lines, the better.

However, cinema is a visual medium. It’s arguably at its best when the audience is gripped by compelling imagery and action, and this needs to be described on the page.

Take Ernest Lehman’s script for another famous Hitchcock sequence: the crop duster scene from North By Northwest. It’s packed with the kind of dense description that executives supposedly don’t want to read.

Writers are often also told not to use parentheticals to indicate how lines of dialogue should be spoken. This allegedly annoys actors so much that they cross them out in the script.

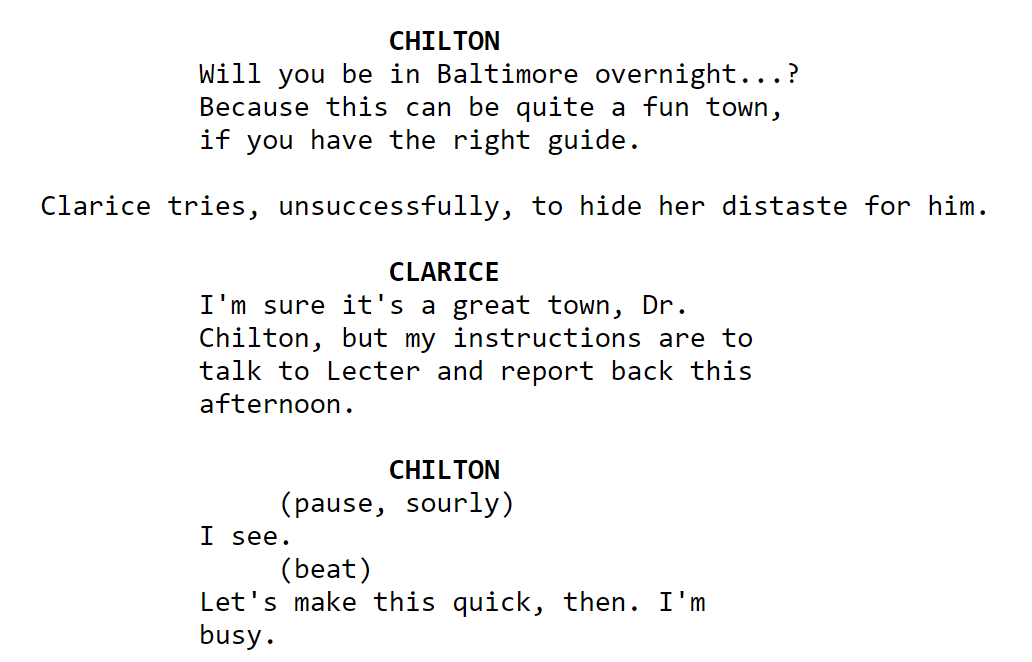

The use of parentheticals in Ted Tally’s Oscar-winning screenplay for The Silence Of The Lambs, clearly didn’t bother Jodie Foster and Anthony Hopkins, on route to their own Academy award-winning performances. The script is littered with them.

In this example, the parentheticals after Chilton’s dialogue are essential. Without them, Chilton’s “I see” line would seem bland and his annoyance at being rebuffed by Clarice, which informs his subsequent behaviour, wouldn’t be clear.

This is another rule I personally find frustrating. It comes from a belief that if a screenplay isn’t perfectly formatted, script readers and industry gatekeepers will reject it, without even reading it.

As a script reader myself, I know this isn’t true. If I passed on a great screenplay on the grounds that the writer hasn’t formatted their scene headings properly or has used the wrong font size, my colleagues would look at me as though I’ve grown an extra head.

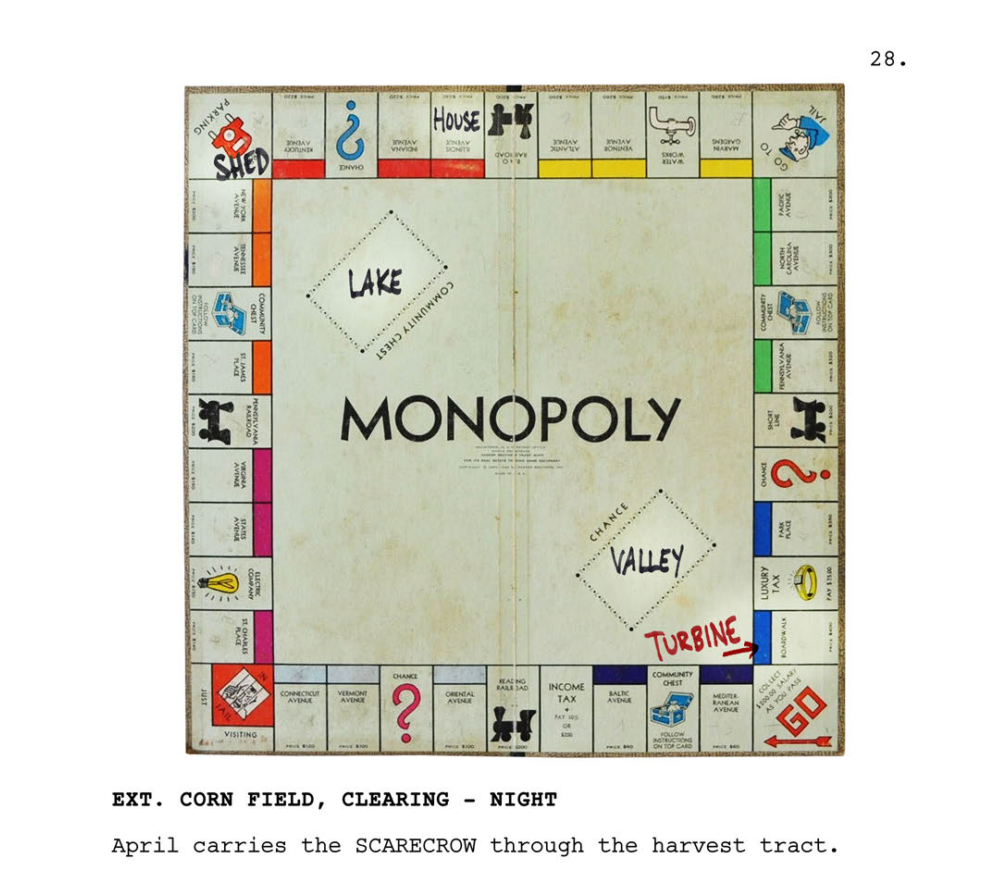

To get around the issue of executives not liking dense description, with a script that had to be almost entirely visual, the original writers of A Quiet Place, Scott Beck & Bryan Woods, included everything from handwritten text and single words on a page to a picture of a monopoly board.

Just as actors apparently object to parentheticals, directors allegedly will react adversely if they feel a script is telling them how to direct the film.

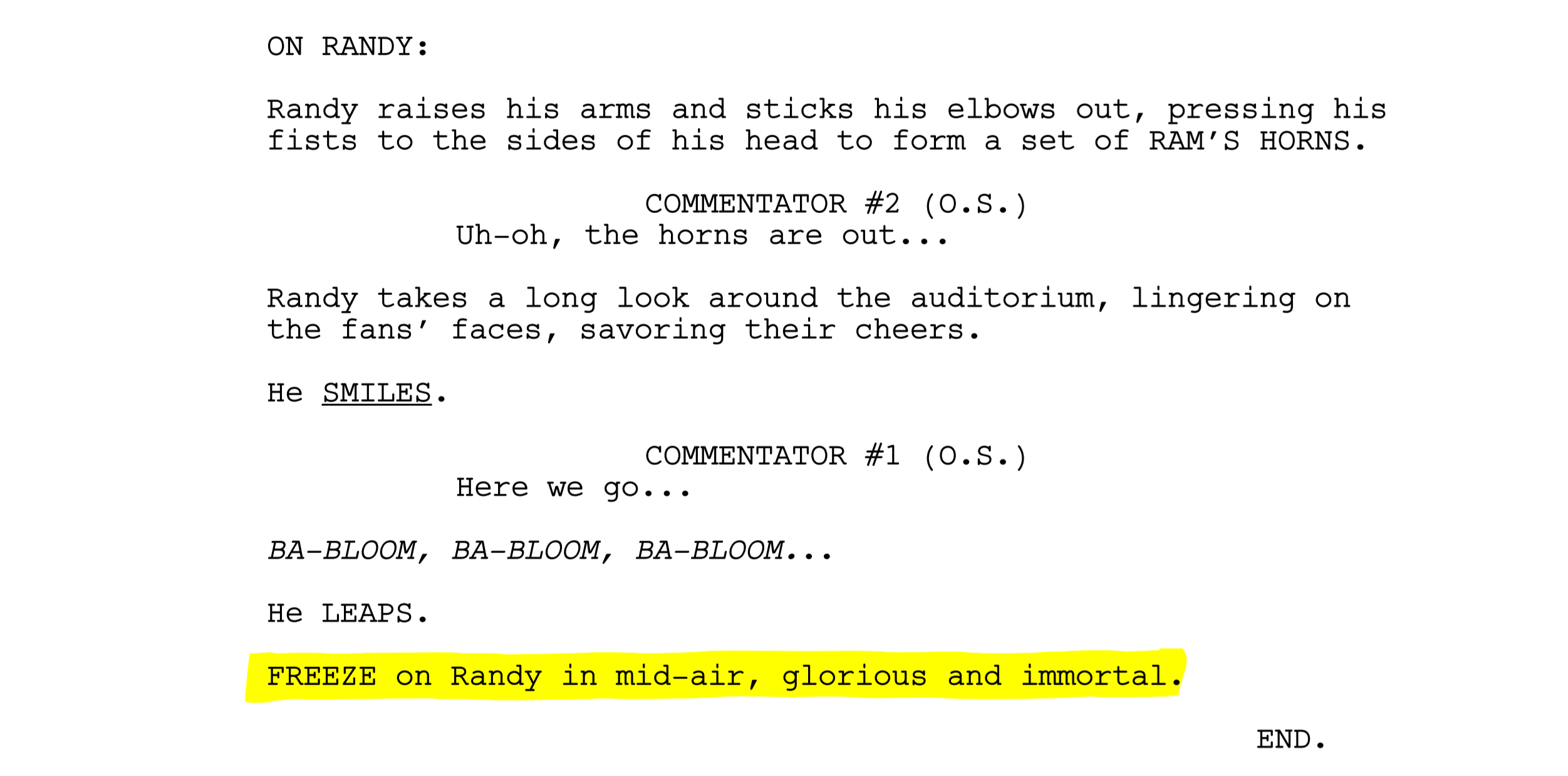

It is true that scripts shouldn’t be filled with technical terms describing specific types of camera shot or camera movements. Sometimes, though, you need to describe what a shot will look like to convey what watching the film will feel like.

The last line of Robert Siegal’s screenplay for The Wrestler could be described as directing on the page, but without it, the script wouldn’t capture how powerful the film’s final moment is.

This gets to the heart of what actually matters. A screenplay should capture and convey the experience of watching the film. Screenwriters can follow or ignore whatever so-called rules they want, providing they accomplish this.

I discuss issues like this with writers from around the world, once a month at the CenterFrame Script Club. If you’d like to join us, you can find out more here.

LUKE FOSTER

Development Executive | CenterFrame Team

Luke Foster is a screenwriter and Development Executive for Iron Box Films. He wrote the horror comedy Ravers, which premiered at FrightFest 2018 and was released in 2020, including theatrically in North America. He also wrote the comedy drama Betsy & Leonard, for which he won Best Original Screenplay at the Madrid International Film Festival in 2013. Luke hosts the monthly CenterFrame Script Club and has a video essay series on horror filmmaking, Alive In The Morning.

Related articles

You can edit text on your website by double clicking ely, when you select a text box

You can edit text on your website by double clicking ely, when you select a text box

You can edit text on your website by double clicking ely, when you select a text box

You can edit text on your website by double clicking ely, when you select a text box

You can edit text on your website by double clicking ely, when you select a text box

You can edit text on your website by double clicking ely, when you select a text box